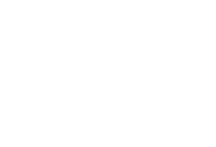

Venue: St John’s Church, Keswick

Date: Saturday, 02 August 2025

Artists: Wordsworth Singers, Dida Condria (piano), Andy McTaggart (conductor)

For a concert titled Summer Light, it was hard to imagine a better Lake District day for this programme celebrating light, love and sunshine – a beautiful summer’s day bathed St John’s Church in warm rays and welcomed a visit from Cumbria’s premiere chamber choir, The Wordsworth Singers. The good weather also beckoned a large audience for this early evening performance, and they were treated to a broad mix of repertoire from Bach to Whitacre, and much more in between.

The concert began in a stylish fashion with American composer (and former student of this reviewer) Sarah Rimkus’s arrangement of the heartfelt gospel tune Shall we gather at the river? Rimkus’s arrangement featured slowly moving clusters of choral sound and prominent solos to wrap this melancholy tune in her own music. To enhance this effect, the choir began in a horseshoe around the audience, the solo and massed voices gathering together in congregational harmony. This was followed by a giant leap into the Baroque era for a collection of well-known pieces by Bach and Handel, beginning with the most recognisable of the lot, ‘Zadok the Priest’ from Handel’s Coronation Anthems. This was delivered with ample pomp and ceremony, accompanied thoughtfully by the wonderful pianist Dida Condria. The main event was Bach’s Magnificat in D, a substantial piece that gave plenty of opportunity for the choir, soloists from the group and accompanist to show their musicality. There was much to commend here, particularly soprano Catherine St. Ville’s solo in the aria ‘Quia Respexit’, all of which was expertly shaped by conductor Andy McTaggart.

The second half of the concert was more varied, beginning with contemporary favourite Lux Aurumque by Eric Whitacre in which the light and gold of the text were captured beautifully by the choir. Lili Boulanger’s Hymn to the Sun gave a Gallic air to the proceedings and again gave pianist Dida Condria plenty to do (she had contributed two sublime solo Bach arrangements earlier), this followed by two very different settings of Robert Burns by James MacMillan and James Mulholland, all warmly introduced by McTaggart. Rapturous applause from the audience gave way to a short encore, a Gaelic Island Spinning Song, arranged by Stephen Doughty which brought the concert to a fitting conclusion. The Wordsworth Singers return to action in November with a performance of the seminal work, Vespers by Rachmaninoff – one not to be missed.

PAC

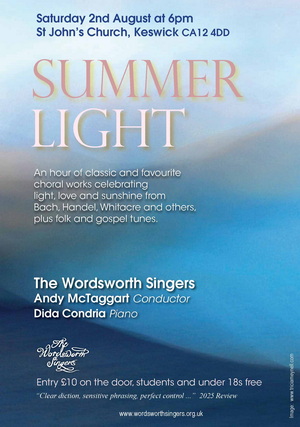

Director Andy McTaggart displayed full confidence in The Wordsworth Singers when he chose to open the concert with Samuel Barber’s Reincarnations. Mary Hynes, the first in this triptych of settings of poems by James Stephens, demands instant commitment from the first moment of its dramatic opening and unaccompanied lines marked allegro and forte. Only a very accomplished choir could be trusted to carry this off – and they certainly did. The second setting, a lamentation for a fallen hero with sustained chanting on repeated notes was most moving and, for me at least, the music suggested images of grief-stricken mourners, scenes all too familiar in current news reports.

Throughout this whole programme of 20th and 21st century American choral music we were invited to dwell on eternal themes of humanity – love, loss, faith, peace – with settings which transform and expand our understanding of the texts. The choir rose to this challenge magnificently with clear diction, sensitive phrasing, moments of great drama and of perfect stillness. All this applied certainly to the Three Songs by Philip Glass. These too are a cappella works with total exposure in every section of the choir. The singers moved seamlessly from the beautiful chorale-like opening section to the energetic hypnotic repetition we have all come to expect from Glass. This must have been fun to rehearse!

In Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms we had the joy of experiencing the wonderful piano playing of Dida Condria. With her amazing technique she convincingly recreated the required explosive and exhilarating effects in her own reduction of a work scored for large symphony orchestra including multiple percussion. A joy too was Dida’s sensitive harp-like accompaniment to the setting of Psalm 23 for which the soprano soloist’s pure tones were well suited. Overall there was a lovely sound balance, but there were times in the first half of the concert when the highest forte soprano lines detracted. One other observation is that singing Bernstein’s complex work in Hebrew slightly inhibited the otherwise total attention afforded to the director.

Morten Lauridsen’s triptych Nocturnes includes a hauntingly beautiful and unaccompanied setting of Chilean poet Neruda’s love poem Soneto de la Noche. Andy McTaggart achieved perfect phrasing, perfect endings, perfect control. One sensed, not for the only time in this concert, a profound stillness in the audience as they experienced something very special indeed.

Dida Condria’s one solo piece, Scottish Legend by Amy Beach was accessible and attractive and her performance was warmly received by the audience.

I had been given details of the whole programme in advance, so had been able to gain some familiarity with the music and the all-important texts. Otherwise I might have felt overfed on too rich and complex a diet of unfamiliar works. Instead I am grateful for what was a most inspiring and memorable experience.

The concert ended with the heartbreaking and beautiful Good Night, Dear Heart, an elegy to a dead child in an unaccompanied and simple setting by contemporary American composer Dan Forrest. Nothing could have followed that.

Juliet Rowcroft

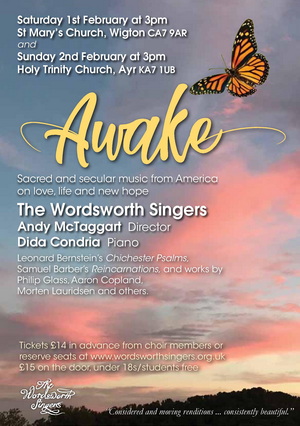

This was held in the Chapel of Austin Friars School whose resonance entirely suited and enhanced the sound achieved by the Wordsworth Singers under their new Conductor, Andy McTaggart. The programme was a challenging one for unaccompanied voices and consisted of nine pieces by twentieth and twenty first century composers exploring a range of emotions based on love, grief and hope.

The opening piece was ‘Mater Dei’ by Sarah Rimkus. This demanded a blend of the underlay by the male voices with the overlay of the sopranos and altos. The blend of voices achieved by the choir was enhanced by the vaulted ceiling of the Chapel to give a tremendous sound. This was followed by two works from better known English composers: Vaughan Williams’ ‘Echo’s lament for Narcissus’ and John Tavener’s ‘Mother of God, here I stand’. Both were given considered and moving renditions with the voices in the Tavener beautifully reflecting the solemnity of the words. This may have distracted slightly from James MacMillan’s ‘A Child’s Prayer’ where the choir provided a lovely sound with real poignancy portrayed in the upper voice ranges, but the words were more difficult to distinguish. Finally, the first half concluded with Eric Whitacre’s ‘When David Heard’. Here the music was particularly challenging, but the dynamics achieved by the choir emphasised wonderfully the grief of David for Absalom.

The second half started with MacMillan’s version of the ‘Miserere’ of which the best known is that of Allegri. There were some hints of this in the chants, but thereafter differed in its dynamics and the way in which the voices were blended. Compared with some of the other works this was more straightforward, but the choir showed a mastery of the composer’s melodic approach. This was followed by Vaughan Williams’ setting of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 71. Here it is vital that the words are fully heard in order that the meaning is truly understood. This was achieved with some lovely clear sounds which did suitable credit to the writing of the composer. A second piece by Whitacre paid homage to Queen Elizabeth I. The very first line talks about the spirit soaring and this was brought out by the sopranos ably supported by the other parts, providing a fitting tribute. The evening concluded with ‘Alleluia’ by Randall Thompson. The introspective nature of the work which relies on a continuous repetition of the word ‘Alleluia’ was a response to the fall of France in World War II but seemed entirely suitable for the times in which we live. The choir managed to impart the feelings expressed in the music with changes in rhythms skilfully handled to achieve a forceful climax followed by the dying away of the Amens.

The Wordsworth Singers appeared to respond eagerly to their new conductor. This was enhanced by the way in which the choir were shuffled in terms of their positions to help achieve the required sound for each work. The overall performance was consistently beautiful and reflected the emotions each composer wished to express. The concert was an impressive achievement and marks a positive development under the leadership of Andy McTaggart.